Notes on viewing a documentary about a Pulitzer winning writer and his privacy seeker Petrarchan friend.

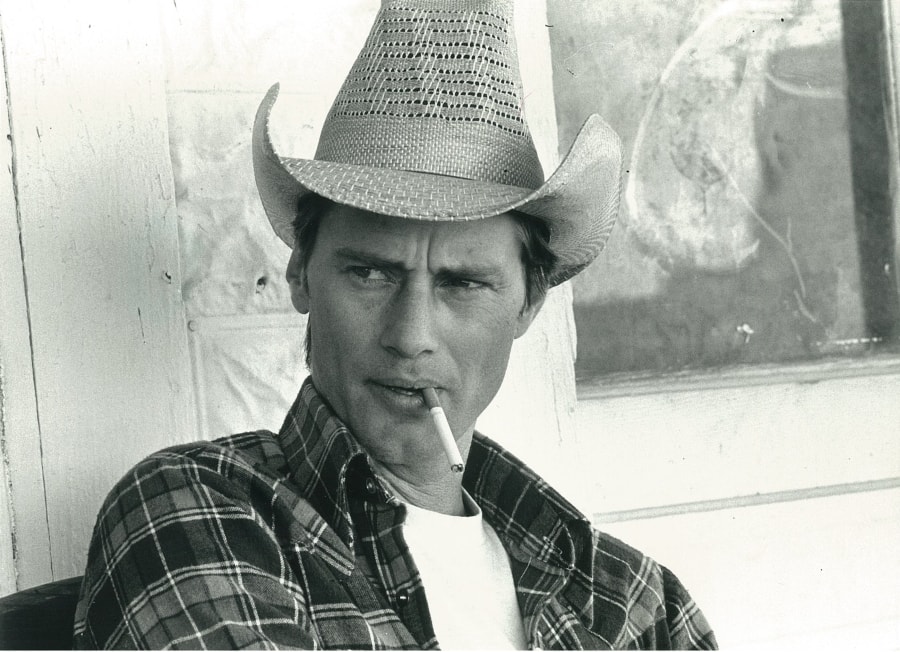

Pulitzer winning writer Sam Shepard inspired me with plays like Cowboy Mouth and A Lie of the Mind inspired me as an actor in the 80s. Now 40 years later. and eight years after his death in 2017, I happened upon a documentary I didn’t know existed about a very private part of Shepard’s life. Even better, he talks about his process as a playwright opening his notes scribbled on the ragtag pages of a journal for A Particle of Dread, premiering in NY in 2014, a title inspired by a line from Oedipus Rex .

Shepard and Dark (2012) embarks on a friendship between creatives; between 1963 and 2012 Shepard and another writer Johnny Dark correspond the old school way at first by the U.S. post office and later use digital forms of communication.

The men’s relationship evokes the Beat Generation’s ethos. Dark explains that he was creatively emboldened by Jack Kerouac and they both illustrate the dilemma of young men of the 50s coming from difficult father/son dynamics. Art and the world of culture became another choice for Sam and Johnny as they moved away from the patriarchial hold of the American masculinity myth and power structure into the emergence of the free love movement of the 60s. Meeting during this time may explain the unexplainable according to Shepard. His enduring communication with Johnny, exactly opposite in demeanor, might be the underlying kismet that fuels this film.

Moreover, director Treva Wurmfeld weaves into their story narrative a spectacularly subtle master class about Shepard’s writing and editing process. During the course of the 1 hr 32 min docudrama shot by Wurmfeld in a style reminiscent of cinema verite edited together pieces of each man’s personal journey while weaving in the relationally grounding manner in which the decades spanning liaison has brought them to what Shepard claims is a financially motivated project at its core.

Regardless of the impetus for participating in the documentary, he delivers genuine artistry developed through his work on 58 plays, memoirs, essays, and short stories. Stumbling on this ongoing interview I find myself scrubbing the timeline in reverse to that minute 11, watching the moment by moment of a chaotic volume of handwritten ideas peeled onto the crisp white pages of his final play, a return to the historic father/son tragedy.

As much as Shepard’s plays such as Buried Child inspire me to act, his last of two novels, The One Inside makes it easier to plumb the subconscious for parent/child truths by splaying them out for the reader as fiction. Of course, the literary is not always literal and in that schism between what is real and what isn’t I find it easier to allow personal experiences of familial trauma to emerge.

Probably without reading The One Inside, the footage of Shepard with his Fulbright Linguistic father’s fellowship award and the Lear analogy the filmmaker provided wouldn’t contain the gravitas that it does. As such, the distinctions between the father and son are poignantly a contributing factor to how I will read Shepard’s work in the future, albeit from a writer’s perspective this time around.

(At the time of this post you can view it free at:

https://fawesome.tv/movies/10640942/shepard-dark

The doc is also available on Amazon.

– a.h.

Leave a comment